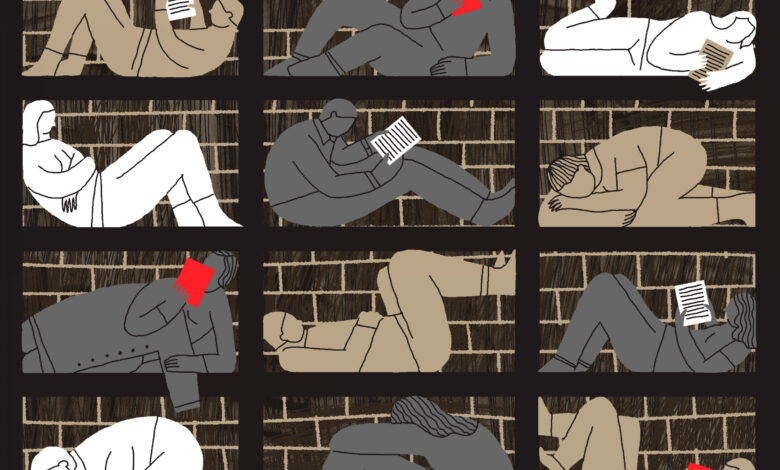

Torture in stress positions, beatings, unsanitary conditions: what Belarusian women face in prisons

The Human Rights Center Viasna has submitted information to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, providing details on instances of cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment, as well as torture, inflicted upon women in Belarus.

Human rights defenders compiled the data while documenting instances of torture and ill-treatment perpetrated by the Belarusian authorities and other individuals in the lead-up to the 2020 presidential election and beyond. The Human Rights Center Viasna has obtained the informed consent of victims and witnesses for the anonymous use, publication, and transfer of the received information to the UN human rights mechanisms. Over the course of three years and five months, records were kept for a total of 193 women. The stories of 106 women include details about their apprehension and subsequent detention in places of deprivation of liberty. All of them faced violations of their human rights, and these violations occurred without considering their vulnerability due to their gender.

Thirty-seven women reported instances and described specific circumstances of physical abuse during their arrest and detention. When recalling their experiences of being arrested, the women recount incidents of being struck on the legs with a police baton and subjected to beatings while lying on the ground. While one of the women was being beaten, a silovik mockingly declared: “Consider this a lesson for all your stones [allegedly thrown during the protests] and Molotov cocktails. I’m here to teach you how to live and show you what being paid to protest will get you.” He also addressed her using the derogatory term “bitches” in the plural.

Many women experienced severe mistreatment as siloviki broke into their houses and apartments and conducted searches. The interviewed women report injuries sustained as a result of the harsh arrest process. These include an arm fracture with four bone fragments and accompanying nerve damage, deep hematomas, a closed patellar fracture with displacement of bone fragments, damage to the ligamentous structure of both elbow joints, and numerous abrasions, bruises, and contusions.

The women reported experiencing psychological pressure from siloviki during their arrest and detention. They also provided testimonies about threats of sexual violence they had received. In addition, the women were threatened with having their parental rights revoked, putting their children at risk of separation from them. Nearly all women reported experiencing emotions of fear, shame, and humiliation, coupled with an unstable psychological state following their release.

Eighteen women reported being subjected to torture through enforced stress positions during their detention. They were made to maintain uncomfortable and unnatural positions until they could not continue due to exhaustion. Five women shared that they had experienced “music torture” during their detention, involving the loud playing of music that hindered their ability to sleep, calm down, or recuperate. Many were either denied medical care altogether, or the care provided was of subpar quality and insufficient in quantity. All the respondents brought up the unsanitary conditions of their detention and the lack of hygiene items.

The absence of adequate medical care quality and the unsanitary conditions in detention facilities further exacerbate an already challenging situation. The intentional withholding of proper medical care or substandard provision of such care, and the absence of essential hygiene products represent grave violations against the established health care standards for detainees. In 2021, female political detainees at the Akrestsina detention center went on a hunger strike, citing the unbearable conditions they were facing.

No doors on standalone toilets in the cells, male guards in prisons and detention centers – is this not discrimination against women?

In the cells of the Akrestsina detention centers, women couldn’t avoid constant surveillance from continuously operational video cameras, even during private moments like using the toilet or maintaining personal hygiene. In the Zhodzina detention center, toilets had no enclosure whatsoever, leaving detainees no privacy, and cells lacked access to hot water. These conditions allowed male staff to observe detained women even during their most private moments.

Political prisoner Volha Klaskouskaya, who served 791 days in prison, shares her insights on the “correctional” aspect of the Homel penal colony system:

The penal colony administration intentionally sets up conditions to kill a woman in you and to extinguish any inclination for self-care. It’s because when you realize you look good, it lifts your spirits, and you are not supposed to be happy in that place. You are supposed to be this gray mass, you shouldn’t smile: as many prison staff members would put it, “prisoners should feel hungry, cold, and damp in prison” as a natural extension of their belief that “prisoners should suffer”. These beastly conditions are all very well thought out and carefully realized to completely knock the ground out from under your feet so that you lose your identity, break down, and experience a decrease in morale. Every effort is made to paralyze your will, to eradicate any thought of resistance. To make you feel weak, inferior, helpless, and guilty, as such individuals are more susceptible to control and are easier to manipulate.

Numerous transfers from one detention place to another, along with insufficient nutrition, loss of appetite, and constant stress, eventually led to a substantial weight loss: I dropped over 15 kilograms. Furthermore, my hands were shaking violently due to severe bleeding and, consequently, low hemoglobin levels. When in the prison canteen, I struggled to eat soup as my hands trembled to the point where I couldn’t even hold a spoon. Over time, I resorted to drinking it directly from a plate – or whatever that aluminum contraption was that passed for a plate.

Four toilets for 100 people

Sometimes, I didn’t have the time to use the toilet in the morning, given that we only had four toilets for 100 people. Time is very limited: you get up at 6:00 am and are expected to be ready for breakfast by 6:25 am. Before that, you must make the bed following some incredibly idiotic requirements. We had to tuck the blanket into the sheet like an envelope, ensuring specific distances in centimetres between the corners of the envelope. At the same time, the visible width of the middle section of the blanket tucked into the sheet should be no larger than the size of a matchbox. And you also have to get dressed and go to the toilet, but there’s a queue. Queues are everywhere, and everyone is angry in the morning. It wasn’t always possible to get to the toilet, and as a result, my stomach ached very often. One should go to the toilet after waking up in the morning; it is just natural, but this opportunity was frequently unavailable. So, I would usually use the toilet at the factory where I worked.

Volha notes that the harsh conditions the prison administration created have a detrimental impact on the health of hair, skin, and nails:

Many started losing hair due to an unbalanced diet, lack of vitamins, and chronic stress. There is no time for a thorough wash in prison. You’re essentially just spreading dirt on yourself instead of washing it away, so to speak. The shampoo cannot be properly rinsed out of your hair. This significantly impacts the condition of your hair. This certainly is a form of derision not to allow a woman to wash her hair and, generally, to deprive her of the opportunity to wash properly. We would wear a head covering almost all the time, causing our heads to sweat, especially during the summer. The head itches constantly, the hair is always dirty, and dandruff crops up.

Twenty-year-old former political prisoner Darya Karol describes the detention conditions in the Akrestsina detention center:

They would give us a quarter of a laundry soap bar once a week. It served all purposes: washing dishes, hands, and laundry. Sliced toilet paper was also provided for the day, but it was in short supply. The situation with sanitary pads was complicated. There was once a case when two sanitary pads were distributed among three people for the entire day – how were we even supposed to get out of this pickle?! Therefore, we always asked for sanitary pads and collected them for future use. During the evening searches, our bags were turned inside out, and sanitary pads were shaken out of their wraps.

The analysis of the documented stories indicates severe violations of women’s rights and instances of abuse. The evidence presented highlights the pressing need for an international response to the practices of detention and imprisonment in Belarus. This response should prioritize the protection of the rights and safety of all detainees, with special attention to those facing heightened vulnerabilities, such as women.