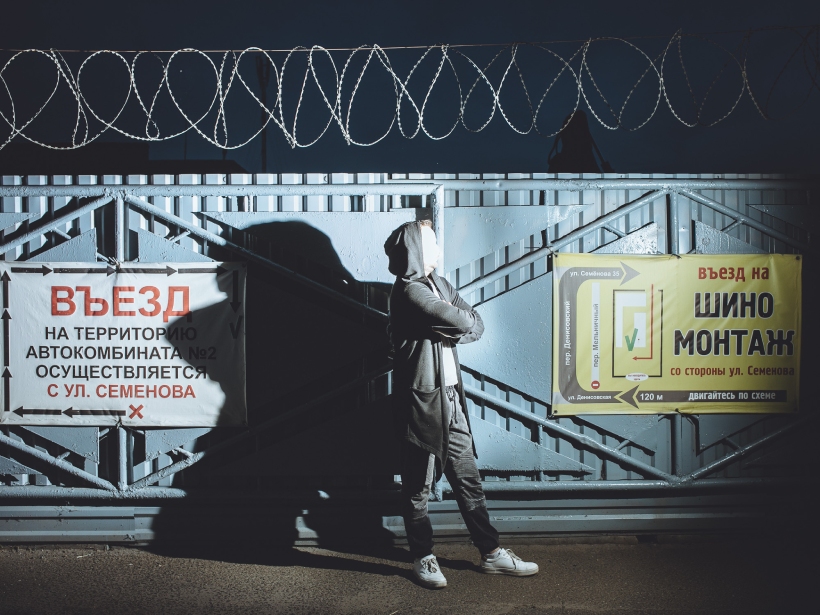

Torture and abuse in 2020 – story of Viachaslau

29 years old, traumatologist. “I have seen all kinds of wounds, but I’ve never seen such violence.”

Viachaslau (name has been changed at the request of the interviewee) is a traumatologist. After the presidential election in August 2020, he volunteered at a Minsk hospital and worked at a volunteer camp near Zhodzina. He saw with his own eyes the injuries sustained by the victims on the streets, in prisoner transporters, in the Akrestsina detention center, and in Zhodzina: bullet and shrapnel wounds, massive hematomata, contusions, head injuries, baton blow marks on their torsos, buttocks, and all over their bodies. After everything he had witnessed, Viachaslau changed his attitude toward the police fundamentally.

“We are balancing between fear of and hatred towards our predicament”

“I had an agreement with the trauma center: they would call me if they needed me. But the Internet access was blocked, the news was alarming, and I couldn’t stand this anymore: I went to the center around 11 pm. ‘Have you come to hide, too?’ my colleagues joked. All the doctors, nurses, interns, and trainees were on duty in hospitals that night. Not a single person was sitting this out in their office. Everyone was waiting nervously next to the ambulance bay. At times, four ambulances would arrive at once, even though our hospital was on reserve. The patient flow was mostly directed to the Minsk city emergency hospital (BSMP), the neurology center, and the main military hospital.

Everyone realized that there would be clashes [between protesters and security forces], but no one was prepared for bullet and shrapnel wounds

Everyone realized there would be clashes [between protesters and security forces], but no one was prepared for bullet and shrapnel wounds. It was like something out of a movie. We heard explosions and saw flashes. I treated and stitched wounds. I even thought about going downtown with a first aid kit, but the traffic was blocked in that direction, so I went back. These three nights morphed into one endless night. I would come home after 4 am.”

Viachaslau flips through the photos on his phone: there’s a photo of a man who has a bullet mark the size of a 5-kopek coin in the heart area. Viachaslau says that if the man had stood any closer to the weapon that had discharged the bullet, the consequences would have been dire. Some escaped by scaling fences and were injured in the process; some shielded themselves from truncheon blows, and their arms and hands were literally a bloody pulp. Patients with the most severe injuries or conditions were taken straight to the operating room. There was a man with a shattered heel. “Can you imagine,” says Viachaslau, “there is nothing where his heel should be, just fragments of bone, flesh, and skin.”

There were patients with bullet wounds. One person had a rubber (almost as hard as plastic!) bullet in his thigh; the patient took it out himself while still in the ambulance and put it in his backpack. The doctors were eyeing this “trophy” with amazement: no one could have imagined that peaceful unarmed citizens would be shot at.

“There was that one guy who had his eyebrow cut stitched. He and his father went to a store in the evening: his father was taken away, and the guy himself was beaten up. What was most striking was the psychological state of the people. They had been afraid of us until they saw our white bracelets. All the doctors wore white ribbons and tried their best to say: ‘Don’t be afraid, we are not enemies.’ At that time, it was unclear who was on which side. That’s why not everyone was willing to go to a hospital. We contacted medical professionals we were acquainted with and asked them to bandage people’s injuries at home. This was almost too much. But people didn’t even trust doctors, they were afraid the doctors would turn them in.

And at first, we advised those who weren’t afraid to seek medical assistance to write in their statements that they had been injured in domestic accidents so that the Investigative Committee would not look for them. Then, after a couple of days, we came to understand that this could not and should not be hidden and that all the traumas had to be documented. But even then, we were afraid for people. We were afraid that the matters could be made worse: the Investigative Committee later requested that trauma centers share the names of all the people who had sought medical assistance around that time.”

The doctors were no less shocked than the victims. The atmosphere was very tense. People of all ages were admitted to the hospital. And everyone was scared. They were afraid to go home. Some people were offered an overnight stay at the hospital. Viachaslau drove patients home every night after his hospital shifts were over. And then, after the Internet access had been restored, an avalanche of three days’ worth of “war reports” hit people. Mothers searched for their sons, and wives searched for their husbands in hospitals, morgues, police stations, and prisons. Volunteers compiled lists of missing people. On that day, hundreds of women clad in white and carrying flowers lined up in a human chain to protest the security forces’ violence.

It was impossible to remain apolitical after all I had been through. Even my mom went out to participate in peaceful protests

“When I saw women with flowers, I cried. Before that, I would return home from the hospital feeling emotionally drained. I don’t remember any impressions from that time. It’s like I was in a constant state of shock. It took me a while to realize what had happened. It was impossible to remain apolitical after all I had been through. Even my mom went out to participate in peaceful protests. She called me and said: ‘I’m at Pushkinskaya [subway station].’ She said she couldn’t look us, her children, in the eye otherwise. She has four of us.”

That’s when doctors in white coats were spotted in the solidarity chains. According to Viachaslau, it happened spontaneously. Although the health minister called the medical workers’ protests “orchestrated”.

“We gathered outside the Belarusian State Medical University (BSMU) to discuss leaving our trade union, which didn’t bother to defend the doctors who had gone through the wringer. Our white coats served as some sort of a meeting pass. People holding flowers were already lining up along the avenue. And we joined this spontaneous protest action while waiting for our colleagues. The health minister (now ex-minister) Karanik arrived within moments. He passed swiftly through the crowd and made a hand gesture as if saying: ‘Everybody, follow me.’ But no one followed him: ‘If you want to talk, let’s have a chat right here.’ A couple of minutes later, reporters working for the state-run TV channels arrived. He made a comment to them that he was ready to enter into a dialogue, but it was us who didn’t want to. Then two prisoner transport vehicles pulled up. We decided that if the doctors were to be arrested, it would be the end of everything. But they didn’t touch us that day.”

On the night of August 14, detention centers and prisons started releasing detainees en masse. Upon hearing that medical help was needed, Viachaslau drove to the Zhodzina prison. The people were released at night, four people every 20 minutes on average. Viachaslau stayed there from 6 pm to 9 am.

“There was little need for emergency surgical care, but everyone without exception needed psychological services. Those who were released, those who waited for them, and even we who were just helping out – we all needed psychological help. What have I seen there? All those things that the state media later dubbed ‘buttocks painted in blue’. Hematomas all over an individual’s body: their skin was blue everywhere, from head to toe. Backs with baton blow marks. I’ve never seen such bruising in my whole life! A doctor remembers patients by their medical diagnoses. I don’t remember their faces, but I still remember their traumas. There is no way I can explain these atrocities. I didn’t have time to take photos then, but now I wish I had documented evidence of the beatings.

We all had lumps in our throats and clenched our fists at times. You would have this kind of reaction when a 50-year-old battered man is crying in front of you. He was crying not from pain but from the realization that the whole country had been turned upside down, that he hadn’t just been beaten for nothing, that all this hadn’t been for nothing. You would have this kind of reaction when a 12-year-old girl and her mom spent the whole night next to the prison walls waiting for their dad and husband to be released. Because staying home in the dark was even scarier. I couldn’t wrap my head around the absurdity of the situation. People laid gymnastic mats on the lawns outside the prison walls and spent the night there. I remember a woman who was released from prison and waited another eight hours for her husband to be released. He went out all battered, his knees sore. I remember a mother who finally saw her son. He was battered but, most importantly, alive. She was clinging to him and sobbing. ‘It’s okay. Why don’t you sit here, and we’ll give him a quick check-up,’ we tried to bring her to her senses.

We often had to help people waiting for their relatives to be released because, at some point, they would start exhibiting signs of a nervous breakdown

We often had to help people waiting for their relatives to be released because, at some point, they would start exhibiting signs of a nervous breakdown. Psychologists would approach us all the time to ask if everything was alright. Help came from everywhere. I remember a man who waited six hours to take some of the people who’d been released home. He wasn’t the only one. One such volunteer driver took us home, too. There were a lot of people. So many doctors volunteered that we made a schedule and decided on who would take over for whom.”

“It was like a city in a city. We would leave desks, chairs, and power banks behind for others to use, and write down our phone numbers without really counting on the return of the items. People had brought so many medications that doctors started rejecting them. There were enough medications for three hospitals there. There was a lot of food. At 1 am, a family brought a large cauldron of pilaf they had been cooking for 5–6 hours. The cauldron was this big (Viachaslau spreads his arms). This was some good stuff! It was still hot. Everyone could help themselves to some food. And we had tea in thermoses. We had a lot of water too. Blankets, jackets, shoes, shoelaces. People would bring something all the time. And in exorbitant quantities.”

“The nights were cold. We were wrapping ourselves in three blankets each, and the detainees were wearing shorts, T-shirts, and no shoes at the time of their release. Upon their release, they would be shocked for a split second. They were afraid they would be taken somewhere again. They would see a bunch of people and start checking if there was a prisoner transporter nearby and if there were ways out. And when they realized that so many people had gathered there for their sake, emotions ran even higher – from negative to positive. They were all bruised but happy, in some kind of euphoria.

Everyone had to be comforted. We even had to calm each other down sometimes. All the people who had left the prison walls had high blood pressure: 200/120, 180/100. The adrenaline kicked in due to stress and fear. We gave them pills to lower their blood pressure and treated their wounds. Men, women, and the elderly were all beaten. Some less, some more, but all of them were beaten up. Some had head wounds, but it was too late to stitch them as more than 24 hours had passed. Every other person had diarrhea. They were given water and bread in prison. And for some reason, they could not digest that bread. But they called the prison conditions ‘not bad’. Apparently, the Zhodzina prison was almost like a spa or a resort compared to the Akrestsina detention center. People were treated more humanely here. The conditions weren’t as hellish. While they would put 60 people into one cell at Akrestsina, here, in Zhodzina, there would typically be 10 people in a four-person cell.

Everyone was given water, food, and a hygiene kit with toothpaste and a toothbrush. People were offered blankets and clothes and given an opportunity to make a phone call or get a ride home. And we asked them about whom they had seen, whom they had been in the cell with, and whose names they could recall. The volunteers were constantly compiling lists of detainees sorted by the cells they used to be in and calling the Akrestsina detention center often.

At that moment, the public mood changed: we tried to persuade everyone to document the traumas from the beatings, to make everything public, not to hide

At that moment, the public mood changed: we tried to persuade everyone to document the traumas from the beatings, to make everything public, not to hide. After all, some people were not even asked to provide passport info. That means they were not even on the lists. Lawyers consulted people about filing claims and advised them on where and how to go about this.”

“It seems that every single Belarusian now has an acquaintance or a relative who had been arrested and spent some time behind bars. Every other person was taken into custody during the protests. I’ve attended almost all the protest rallies. I’ve had to run from riot police, too. I developed a sense of civic duty and responsibility after the presidential election. How could you sit this one out at home in such a situation? Even those who couldn’t go to protest rallies were on duty sitting in front of their computers, notifying us about ambushes, and telling us where to go and not to go. And by some miracle, I managed to not fall into those security forces’ traps.

I always had my first aid kit with me: bandages and hydrogen peroxide. I chose medical science as a profession out of great love for it. I could not understand how one could beat a doctor for their wanting to help. Yet, I didn’t want to stand out in the crowd and be in harm’s way, and therefore, did not flash my white coat or red cross. That said, I know a doctor who was just walking home and ended up in a prison cell. Later, he posted a message in a chat: ‘Previously, I did not believe they could simply detain someone on their way home. Now I can confidently say: THEY CAN. Previously, I did not believe that some anonymous people could give false testimony that one had been out protesting somewhere. But now that I’ve tested this myself: THEY CAN.’

I am living in two worlds. One world is comprised of people willing to see and make changes. The other is those who need to provide for their families and pay their loans, those for whom having a job and something to eat is good enough. Just as long as there is no war. That is why they are silent. Depression and fear are what these two worlds have in common. Obviously, one can’t be ‘on the cutting edge’ of what is happening in society all the time. One also wants to live, love, and watch sunrises and sunsets.

When I go to the city, everything is quiet, and nothing is happening. I live the way I used to, I work, but I avoid the police like enemies. I give a side eye even to regular patrol officers. It’s as if I am waiting for something to happen at any time. It’s not that I’m angry or disrespectful. It’s just that the police don’t ‘protect and serve’, and I’m afraid of them.

There is a new word in the Belarusian vocabulary: the word ‘bus phobia’ is used to describe a feeling when a nondescript minibus happens to be nearby. Protesters and dissenters were pushed into such minibuses and taken to unknown destinations. When driving, I see a lot of such buses around the city. One can’t figure out who’s inside them. I once stopped at a traffic signal and noticed a minibus in the adjacent lane. The driver looked at me and held his phone to his face. I thought for a second that it was a gun.

We are balancing between fear of and hatred towards our predicament. No one expected the situation to be like this. And the worst part is that it’s still ongoing. Days, weeks, months. One reads the news and never tires of being amazed at it. I don’t know where we’re headed. Every time I think that we can’t fall any lower, the speed of our free fall only increases.”

P.S. Viachaslau narrowly avoided being detained several times.

Author: August2020 project team

Photo: August2020 project team